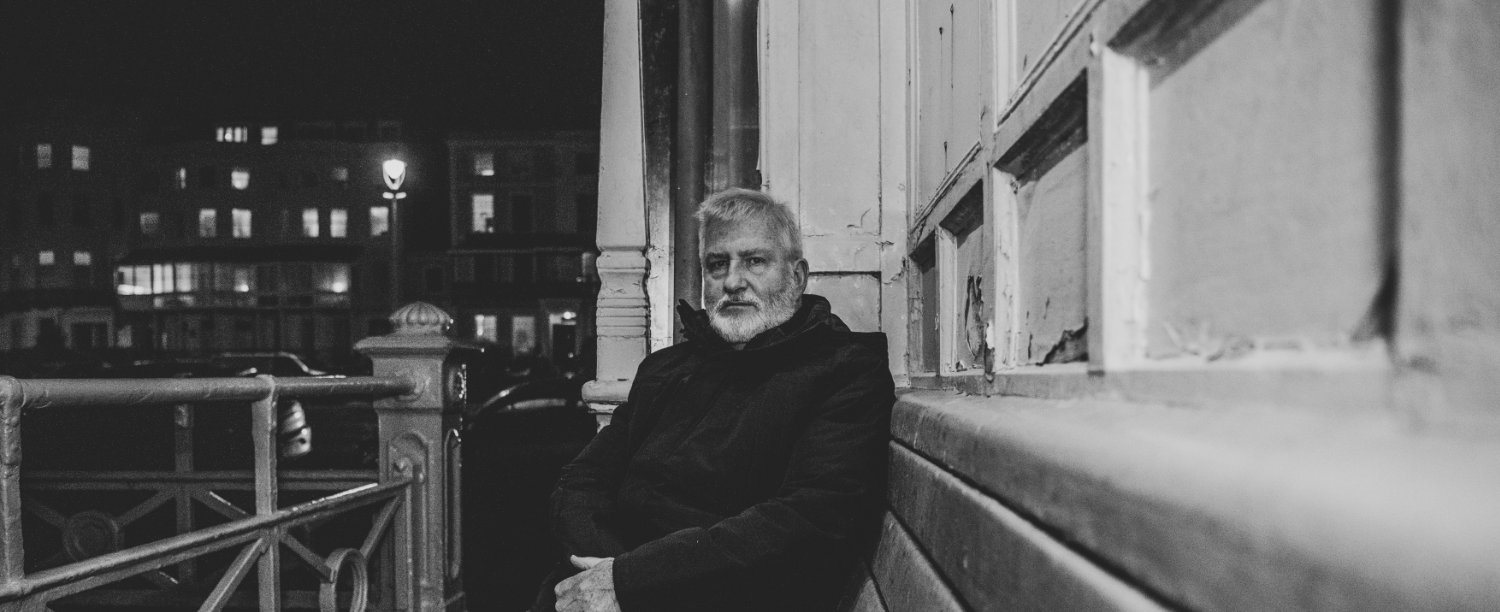

The Column: Eddie Myer – Playing on the Barricades

Whatever your own particular political persuasion, you should perhaps be grateful to the motley crew over at UKIP for galvanising widespread interest in the upcoming Euro elections, a poll most of us have traditionally been happy to ignore completely. Now that their lead in the polls has translated into election results despite their candidates’ own best efforts to shoot themselves in the unreconstructedly chauvinistic feet, perhaps we may even see a productive reaction set in and initiate a return to the heady days of the 1980s when politics were seen as a matter of general interest, like football, and every artist and musician would be expected to firmly identify with a particular camp.

Back in that dim Thatcherite past, rock music was the most audible voice of politicised populism, with Red Wedge on the left lined up against the likes of Phil Collins and Eric Clapton on the right. Jazz’s position at the time was perhaps a little equivocal, as due to the peculiarities of fashion, saxophones, pork pie hats and extended chords had become so associated with yuppiedom that the whole form was regarded with suspicion by the guardians of austere post-punk righteousness, and having a saxophone player in your band was almost tantamount to endorsing the Tory party. At the same time, the multicultural aspects of jazz meant that it continued to appeal to the left-leaning constituency. All of this gave rise to some degree of confusion and conflicted emotions in the hearts of many jazz fans, traces of which linger to this day. Let’s take a look at the relationship between jazz and politics.

It is a central fact of jazz music’s identity that it arose from the culture of an oppressed minority forced to live on the bottom tier of a fiercely capitalist society. The rapid growth of jazz was associated with the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, and as such the music was identified very early in itshistory as a source of African-American pride. However, there is very little trace of overt political consciousness in any of the early jazz musicians or composers,and we can probably infer that the majority were chiefly too concerned with the already tricky business of making a living to want to rock the boat. Come the totalitarian 1930s, jazz was condemned as degenerate music by both Nazis and Communists – the Czech writer and musician Josef Škvorecký, who endured life under both dogmas, has written about the contortions that result when music is forced to adapt to ideology. Communism always had a bit of a problem with jazz, being obliged simultaneously to celebrate it as the voice of the oppressed and condemn it as a hedonistic blandishment of capitalism, which may explain why many left-wingers in America and elsewhere usually felt more comfortable with folk music. By the 1940s jazz was popular and established enough to be enrolled into the US war effort, and many of the post-war post-boppers cut their teeth in military bands, where they were expected to play big band swing as well as marches and reveilles. In fact, the US state department organised many post-war jazz tours of Africa, South America and the Far East as part of their policy of fighting the Cold War with soft power as personified by the likes of Charlie Byrd and Herbie Mann.

Jazz’s great politicisation really took off with the Civil Rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. Billie singing Strange Fruit, Max Roach and Charlie Mingus may have led the way, but many others followed, with even the spiritually-distracted Coltrane naming a tune Alabama after the 1963 bombing. The extraordinary accomplishments of the African-American jazz community were naturally linked to the rising Black Pride movement. As related by Val Wilmer in her book As Serious As Your Life, the free-jazz movement that arose out of the iconoclastic 60s tumult had a heavily political dimension that some may feel tended to rather overwhelm its musical accomplishments. By the 1970s, the political shade of the jazz world had become decidedly red. This was equally true in Europe and the UK, where jazz music was embraced by the radical left as a corrective to the consumerist excesses of pop and rock and the solipsistic musings of the singer-songwriter genre. As with the classical tradition, jazz’s anti-Establishment stance increased in direct proportion to the decrease in its mainstream appeal. Jazz’s status as an art music of dubious commercial viability made it attractive to musicians who rejected the capitalist/consumerist status quo, and its credentials as the music of the oppressed regained credibility, even as the oppressed themselves tended increasingly to prefer other music when socialising or just kicking back. Duncan Heining’s excellent account Trad Dads, Dirty Boppers and Free Fusioneers, already cited in this column, gives a very informed perspective of the ideological struggles of the British jazz scene, with notable mention to such firebrands as Tony Oxley, Mike Westbrook, Keith Tippet and Chris MacGregor. Heining even attempts a Marxist analysis of a jazz musician. (Freelancers can be either Productive or Unproductive Labourers but Bandleaders produce Capital, if you’re interested). Loose Tubes, the hugely influential collective who made an extremely welcome comeback recently featuring our local stalwarts Julian Nicholas and Ashley Slater, carried the radical-left torch into the 1980s. So where do we stand now?

Jazz can be seen as a progressive art form, that values collective endeavour, radical thinking, and creative solutions, and values self-expression over commercial success, and this coupled with its heritage as a music of the oppressed makes its association with left-wing politics, especially of the more middle-class sort, seem a natural fit. Yet for all the avowedly progressive politics of many of its practitioners, the fact is that a large proportion of its UK audience tend to be white, male, middle class and comfortably distanced from the confusions and excesses attendant upon youth, none of which factors suggest a radically-minded fanbase. Thus it’s perhaps no surprise that despite the music’s radical past the one actual serving UK politician most associated with jazz should be the bonhomous, hush-puppied but irreproachably big-C Conservative Ken Clarke (who also shares a name with the baron of bop drumming also known as Klook). Music has often been co-opted into politics but ultimately it tends to confound those who seek to pin it down to any particular cause.

Eddie Myer