Improv Column: Wayne McConnell – The Forgotten Pianist

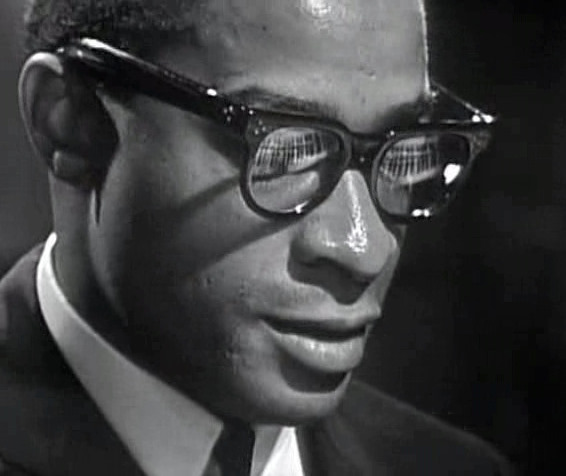

Phineas Newborn Jr. is not a household name like, say, Oscar Peterson or Art Tatum. The simple fact is that he an under-represented genius who was a member of one of the most talented musical families to come out of Memphis.

Origins of the Newborn Style

Realistically, to shed light on Phineas’s style one has to first talk about the pianists who have come before him. His style represents a great deal of jazz piano history and his albums contain documented evidence of the jazz piano legacy from Fats Waller to Bud Powell and beyond.

Phineas’s first influences were those from the stride piano era of the Twenties and Thirties. Jelly Roll Morton, James P. Johnson and Johnson’s gifted pupil Fats Waller all influenced Phineas as a teenager. In this style, the left hand usually plays octaves, tenths or fifths on beats one and three in a bar; while playing chords in the middle range of the piano on two and four. More complex chords (9ths and 13ths) were introduced, then riffs and chromatic runs became part of improvisation. Phineas in his later years (especially on his solo piano albums) often simulated a refined version of stride by playing on all four beats with his left hand, which served as a harmonic support for his solo work and also as an implied stride sound within the trio.

Eventually blues and boogie elements were incorporated into jazz, resulting in the new robust style of the Thirties, Swing. During that decade, Earl Hines’s innovative improvisations, which imitated saxophone or trumpet lines (from Louis Armstrong) influenced many pianists and set the standard for Modern jazz piano. Likewise, Duke Ellington’s unique melodic and harmonic ideas such as chromatically altered chord tones (b5, #5, b9, #9, #11, b13, a clear legacy of Debussy, Ravel and Gershwin), revolutionised jazz piano as well as other instruments. Other noted pianists of the swing style and who greatly influenced Phineas include Teddy Wilson, Count Basie and Nat King Cole.

Next came Art Tatum who literally summarised jazz piano, using everything that had evolved since Scott Joplin. Like Newborn, a true virtuoso, Tatum has influenced generations of instrumental musicians, not only pianists. Impeccable sense of pulse, intricate, long improvised lines, tall chromatically altered chords and syncopated left-hand figures make him the unsurpassed (with one exception) heavyweight champion of jazz piano. Tatum undoubtedly paved the way towards the new style of the 40s – Bebop.

Milt Buckner’s “orchestral” playing (an inspiration to the block chords of George Shearing) may have been a direct influence on Newborn. They did, however; both play in Lionel Hampton’s band. Erroll Garner played a big part in formulating the Newborn touch and style. Garner mixed ragtime, stride, swing and early bebop ideas with an innovative left hand approach in which a bass note and chord simultaneously sounded imitating bass and guitar.

Ensemble playing was also in transition by the Forties. Increasingly, bass players abandoned the old way of playing the root and fifth of the chord and instead began using passing and neighboring chord tones coined “walking bass”. Pianists then had to stay out of the way of bass lines by either playing roots or sevenths (thin “shell voicing” as played by Bud Powell) or modified chord structures imitating the trombone sections of big bands.

Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk were among those responsible for the evolution of be-bop. Adding walking bass to complex, long irregular melodic lines and highly technical improvisations became the norm for horn players. Bud Powell applied this to the piano. Bud was an enormous influence on Phineas as was Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. A great deal of Phineas’s improvisations are in fact bebop based. Phineas had much respect for the musicians from the bebop period – he often played tunes by Charlie Parker (Barbados on Here is Phineas), Bud Powell (Bouncin’ with Bud on Solo Piano) and Dizzy Gillespie (Manteca on World of Piano).

During the Fifties, jazz styles began fragmenting into subgroups such as: Hard Bop (Horace Silver), Progressive Styles (Dave Brubeck who incorporated such Twentieth Century compositional devices as polytonality and asymmetrical meters of 3/4, 5/4, and 7/8.) Funk Jazz which revived the gospel and blues tradition and the joyous drive and feel of jazz associated with it. Hampton Hawes, Oscar Peterson and of course Phineas Newborn Jr. are representative of this style. Peterson, a pianistic giant like Tatum and Newborn, also should be noted as another summarising force in jazz piano, equally at home in all styles from stride to swing, bebop to funk and Latin; as a matter of fact, like Newborn, making almost anything else possible on the piano.

Phineas once described his influences in an interview at Columbia University in 1978 after performing at the Village Gate:

One of my favorite piano players was Nat Cole. He paved the way for lots of exciting things to happen. He influenced me quite a lot. As a matter of fact, I think that’s one reason why Oscar Peterson and I sound so much alike. The same people influenced us more or less. Art Tatum and I enjoyed Bud Powell’s playing. Fats Waller, I liked him very much. He was one of my favorites. I used to do his Honeysuckle Rose.

The Influential Newborn Style

Just as Phineas was influenced by the best of the best, young up-and-coming players are becoming more and more aware of Phineas’s playing. It is players and educators such as James Williams, Mulgrew Miller, Benny Green, Cyrus Chestnut, Eric Reed and Geoffrey Keezer that are continuing the Phineas Newborn Legacy. Apart from sheer technique, these sorts of players have all taken something from Phineas whether it is the orchestral nature of his playing, block chords and of course the double octave technique. The Newborn school of piano founded the double octave technique later used by Oscar Peterson and George Shearing. This way of playing requires great levels of finger/hand independence and higher levels of co-ordination in the left hand. It basically means that you are able to play any phrase with your left hand that you can with your right. By “able” I mean everything including phrasing and articulation! It is becoming almost a normality to be able to pull it off while maintaining swing and phrasing at whatever tempo. Perhaps the best recorded example of Phineas using this technique is from Oleo on World of Piano.

Phineas was a complete master of the piano and on many other instruments. He would often surprise people by borrowing a horn or trumpet at a jam session and proceed to blow away anyone in the vicinity – he even gave George Coleman a run for his money back in Memphis. Phineas was plagued by the critical torment he received from the media calling him “the next Tatum” or “the new Peterson“. All Phineas wanted to do was be respected by other musicians and share his music with others that wanted to listen. A quiet, shy, and introvert man he was very sensitive to others’ thoughts, which led to a succession of ill mental health problems. He was attacked for being too technical and having no soul in his playing. In his later recordings there was evidence of a depleted command of his instrument. Phineas however in my opinion always played with soul (for evidence listen to his own Newport Blues on the album The Piano Artistry of Phineas Newborn Jr).

A racial attack brought him off the playing circuit in 1974. He was admitted to the Veteran’s Hospital with a cracked jawbone, broken nose and several broken fingers. The day Phineas was discharged from the hospital he went to Ardent recording studios and recorded a Grammy nominated album, Solo Piano. The tracks included a version of Out of The World which contained stunning left-hand virtuosity. Stanley Booth says that “hearing that performance while looking at the X-ray photos of Phineas’s broken hands is enough to make you think that Little Red (Phineas Newborn), like Jerry Lee Lewis, is a little more than human.”

The real question is Why wasn’t Phineas given the recognition he rightly deserved? The economic issues of being in Memphis in the Forties and Fifties have contributed to his presence not being in the public eye, and due to the sporadic nature of his recording career Phineas has not claimed the recognition that he deserves. Phineas came up in Memphis at a time where Rock ’n’ Roll was just getting started. Memphis being home to the “King” may have played an important part in the lack of recognition Phineas received. However, aside from the politics and physical obstacles that Phineas encountered, the media has also played a part in the lack of recognising a musical genius. It is only since his death in May of 1989 that the media is recognising his importance to the jazz world – not only to jazz piano but also to jazz as a whole. His musical peers have always known the truth about Phineas.

The Contemporary Piano Ensemble founded by James Williams consists of four or five pianos plus rhythm section. The pianists in the group are James Williams, Mulgrew Miller, Harold Mabern, Geoff Keezer and Donald Brown. The group recorded a tribute album just after Phineas’s death called Four Pianos for Phineas. Each player contributes to the album by incorporating (and showing off) Newborn‘s influence on them. Some of the players do this by song choice, by demonstrating the double octave technique and others by playing in Phineas’s soulful fashion. A highlight is James William’s rendition of a hymn Pass Me Not, Oh Gentle Savior. Phineas had previously recorded five of the tunes on the album while the two originals and hymn are interpreted in the Newborn style.

Phineas was one of those rare artists who embraced the early styles in jazz but also looked forward and participated in things to come. His admirers are as diverse as Oscar Peterson and Joe Zawinul, Charles Mingus and John Coltrane, Andre Watts and Andre Previn. To many others and myself, Phineas was one of the most gifted musical minds in jazz and his recorded work shows clearly his contribution to jazz history.

Listen out soon to the Brighton Jazz School Podcast for an interview with Phineas’s brother Calvin Newborn, the guitarist who taught Elvis to read music!

http://brightonjazzschool.com/episodes/