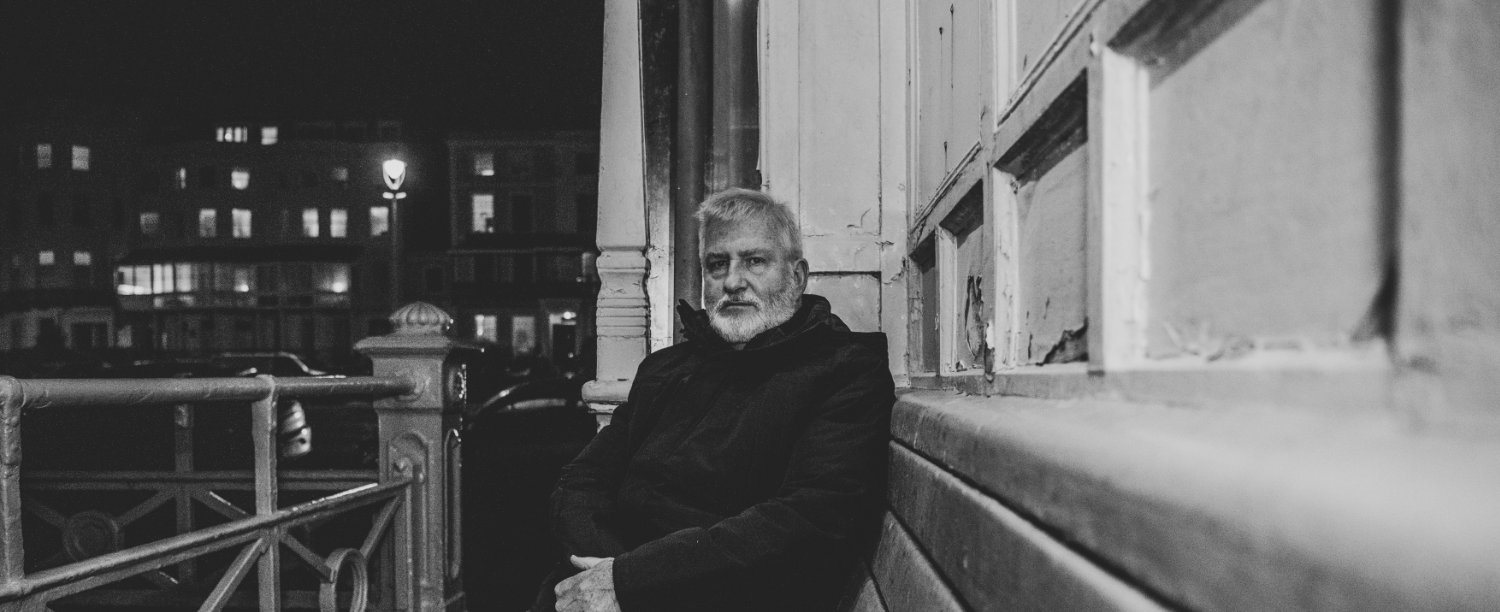

The Column: Eddie Myer – Charlie Haden RIP

This week saw the passing of one of the colossi of jazz, Charlie Haden. All the major papers carried glowing obituaries, paying their respects to the man and his music. Bass players are seldom so eulogised; jazz bass players even less so, and despite having earned the universal respect and admiration justly accorded to a man who’d been at the centre of the jazz world for five decades, Haden might, in some ways, seem an unusual candidate to be so singled out. Both in his personal life and his musical direction, he was something of a one-off.

For starters, while jazz is an intensely urban art form, Haden’s background was not in one of the classic jazz hotspots like New York, Chicago, Detroit or Philadelphia but in the extremely bucolic Shenandoah, Iowa (not to be confused with the Shenandoah Valley immortalised in song and associated with Jimmy Stewart), known as ‘the seed and nursery centre of the world’ due to the dominant local position of the Earl May Seed Company. This same company sponsored a radio programme on which the young Charlie made his musical debut at the age of two, singing in the Haden Family Band. This outfit, set up by his parents and featuring Charlie and his siblings, performed a repertoire of country and folk songs, but under the twin influences of polio (affecting his vocal chords) and a Charlie Parker gig he saw in Omaha, Haden abandoned a nascent career as a country singer and set off for Los Angeles in search of pianist Hampton Hawes. In LA he went to school at Westlake College and managed to gig with Hawes and Art Pepper before a gig with another non-aligned musical radical, pianist Paul Bley, led to an introduction to Ornette Coleman, and jazz immortality.

Coleman had already recorded with impeccable jazz stalwarts Percy Heath and Red Mitchell on bass, but with Haden’s arrival in the band, something really clicked. His style of playing went against the tide of jazz double bass as it was being developed in the early 60s – while Paul Chambers started a progression into ever faster, horn-like high register work, Ray Brown developed all kinds of rhythmic tricks involving grace notes to heighten the swing and funk of his lines, and Ron Carter explored the new possibilities of piezo pickups and steel strings to develop attack and sustain, Haden’s technique seemed plain and old-fashioned. He stayed in the lower registers; his sound was the full warmth of unamplified gut strings; his lines and solos featured each crotchet and quaver clearly and precisely placed, often surrounded by pockets of silence. While the forefront of jazz players were on an ever-accelerating pursuit into greater rhythmic and harmonic complexity, Haden remained primarily concerned with melody and harmonic fundamentals; he’d support the soloist, seldom straying far from the harmonic root; when soloing, he made expert use of silence and never had recourse to repeating jazz licks – either other people’s, or his own – to fill up space. He was a supreme melodist at a time when many felt jazz was abandoning melody – yet his initial involvement was with the avant-garde, first with Coleman and subsequently with his own Jazz Composer’s Orchestra and Keith Jarrett’s classic 70s quartet. All these bands exhibited a ferocious commitment to their music, seeming to reach for a more universal significance than that afforded by the increasing niche world of the jazz club; all received international acclaim, all were rescued from the excesses and indulgences associated with the avant-garde by their adherence to melody, for which Haden must surely take credit. His later career was no less contrary, embracing albums with smooth-picking virtuoso Pat Metheny and his own Quartet West, which eschewed the avant-garde fury of the 70s in favour of lush, romantic arrangements of ballads from the formative pre-war years of jazz modernism. In 2008, he returned to his roots by releasing an album, Rambling Boy, of bluegrass and americana, featuring his son-in-law Jack Black, of all people.

I saw him at Ornette Coleman’s Meltdown festival, where, amongst other things, he performed a pitch-perfect rendition of a Bach cello movement, arco, all in thumb position. He found time to record with ‘hillbilly from outer space’ Beck and straight-edge punks The Minutemen. He really shone in a duo format, recording with a wide range of players from Coleman to Hank Jones, Metheny to Alice Coltrane. He could also, when necessary, swing like a mother at any tempo required. All in all, he was someone who lived his life at the very heart of whatever it is we mean by jazz music in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, yet was never constrained by its seemingly ever-tightening boundaries. I think there’s inspiration there for any who care to look.

Eddie Myer