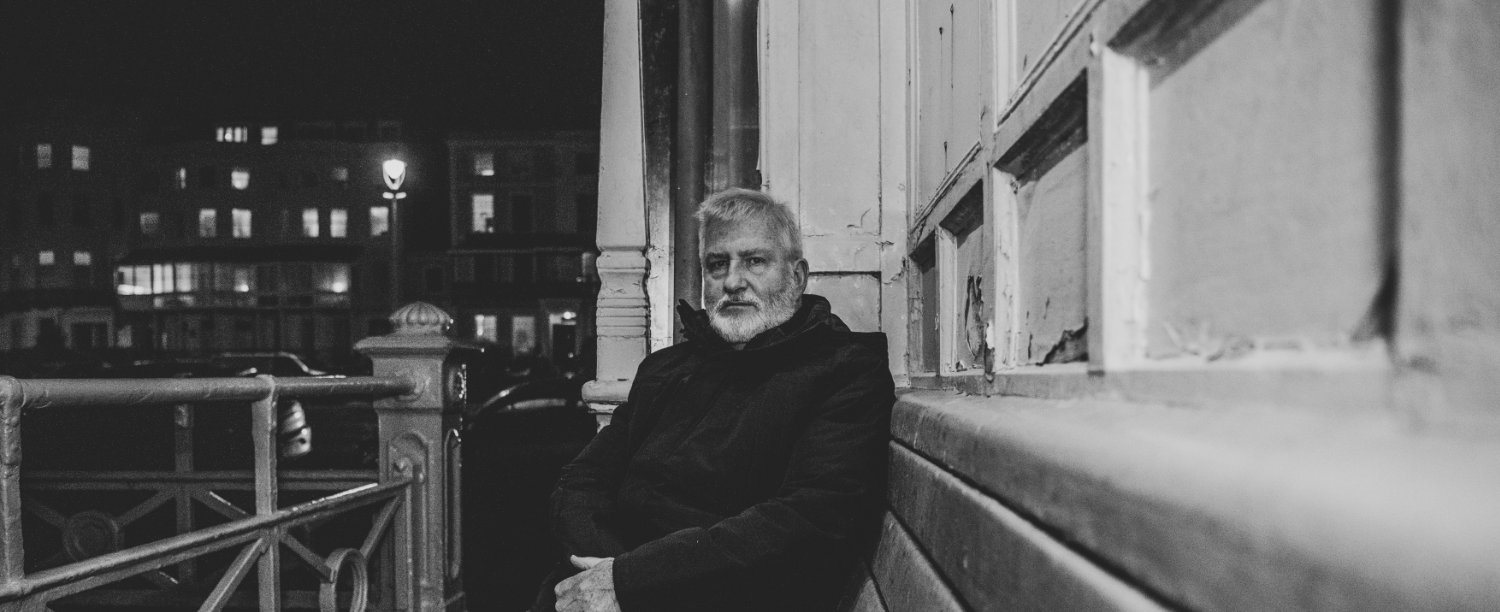

The Column: Eddie Myer – Paying Dues

Spring has arrived, bringing with it the usual panoply of rabbits, lambs, blossom, and, if you’re lucky, seasonal feelings of optimism and renewal. With regards to this last, it’s also brought me a communication from the Musician’s Union regarding their standard pay scale. Those of us engaged in gleaning what we can from the crowded pastures of today’s musical permaculture may be surprised to be reminded that the Union rate for a casual pub or club engagement is £111.00 for an engagement of up to 3 hours, with an additional £55.50 per hour to be paid as overtime if the gig goes on any later. There are, moreover, a wonderful array of what are referred to as ‘Guidance Notes’, including such suggestions as an extra £8.50 per mile distance charge, and an exhaustive list of porterage charges – £25.30 for double bass or electric bass, but only £17.40 for contrabassoon, which seems a little unfair.

As anyone who has been fortunate enough to spend any amount of time with professional musicians will know, the subject of pay and conditions is a popular one during band break time, as is natural in any field where the majority of practitioners are freelancers who have to negotiate their own deals for every job. You’ll also encounter a certain level of professional reticence, making it hard to determine accurate figures for how much everyone is earning, but my totally unscientific research on the subject suggests that even here, in the wealthy South-East, the actual rate for a casual engagement in one of our city’s many lively pubs or clubs is so far below the Union rate as to make the latter look like a work of speculative fantasy. In practice, a sort of organic understanding seems to arise between landlords and musicians as to what the ‘going rate’ should be – a rough figure within which are infinite subtle gradations based often upon nothing more than the persuasive power of either party. The situation in London is much the same: there are more prestigious, and thus better paid, casual gigs to be had, but the Union is seldom party to the negotiations. In fact, the only third party a musician is likely to encounter with any frequency is a booking agent who will be working to balance the interests of both the band and the client in order to secure the maximum number of commissions for themselves. Of course, the landscape changes if the player has a ‘name’ that can sell tickets on the door, and even a manager or personal booking agent of their own, but still the Union won’t be involved in the majority of contracts. Even in the comparatively ordered and regulated world of West End pit bands, my informants tell me that many players are now not even Union members.

Let’s delve a little into the history of the working Jazz musician. Len Goodwin, in his excellent programme “Dance Days”, quoted a Melody Maker article from the 1930s heyday of jazz’s reign as the world’s dominant popular music, claiming that between 12,000 and 20,000 dance bands were operating every weekend in the UK, providing work for up to 100,000 musicians. This was the golden age of the jazz musician as a powerful force in the workplace; yet according to the article the majority of players would still have relied on ‘day jobs’ – a contemporary advert for Selmer Saxophones promotes sax playing as ‘an excellent way to pick up some spare cash’ (while also claiming “You don’t need musical talent to play this Sax”!). In those days recorded music had not yet overtaken live performance, the radio broadcasts were all live, and any entertainment venue worth it’s salt had to employ a regular band. Actual income statistics for UK jazz players are difficult to obtain, but Ingrid Monson’s book “Freedom Sounds” provides a fascinating insight into the working conditions of musicians from the Classic Era of 1950s New York. “A typical nightclub gig in New York in the early 1950s required four sets of forty minutes, with twenty minute intermissions between sets. In 1951, the scale for a sideman working in a New York club was $125 per week for six days of work, with leader paid double scale. The minimum was $20 for the first four hours. By this standard, an extremely busy band member who worked forty to fifty weeks per year could earn an annual income of $5,000 to $6,250 in 1951, substantially above the 1950 average white family income of $3,445.” How much of the history of segregation can be seen in the inclusion of the word ‘white’ in that statistic! However, she adds, “Most jazz musicians worked substantially less than this. A musician who worked ten to thirty weeks a year could expect to earn from $1,250 to $3,750”. The Union Local 802 was extremely active and powerful, as likely to pursue musicians for paying their dues as it was to pursue their employers, and was perceived by many players of the time as acting more in its own interests than in theirs. So even in jazz’s golden age, the living was not always easy. It seems musicians were a byword for improvidence and impecuniosity even then, and the UK Union’s roots can be understood in this context.

Of course, the economics of the music business have changed so much, even in the last ten or fifteen years, that it sometimes seems as if everyone involved is still trying to work out their place in it. The studio recording scene that sustained many musicians has collapsed; the rise in Jazz Academia has only gone some way towards offsetting this. The licensed trade has suffered a series of downturns, from increased rents and beer tax, the rise of rapacious “Pubco” landlords, competition from cheap supermarket booze and the irresistible fascination of the many forms of online entertainment. It’s a sad fact that live music, and live jazz in particular, seldom makes sense in strictly economic terms for smaller venues. The informal rates for gigs mentioned above have not changed for the last fifteen years; if anything the trend is downwards. While a limited amount of support is available from institutions such as Jazz Services, and ‘name’ players with an established following will always be able to command a fee, what are the prospects for the future of the grassroots gigging scene, so essential for nurturing a healthy survival of the music?

One cause for optimism is the general renewal of interest in live music, as the relative value of recorded music disappears down the plughole of filesharing and streaming services. The perception that a great live band provides a unique experience is increasing amongst audiences and landlords alike, as is the acknowledgement that that experience is worth paying for. Though Brighton audiences seem to have developed an unfortunate aversion to paying door charges on the grassroots scene, passing the hat around, like in the folk clubs of Greenwich Village in the old days, seems to be proving an acceptable way of supplementing the take. Many players have taken advantage of the cheapness of recording and duplication costs to make their own CDs, and that helps too. So if you’re out at a gig this week, buy plenty of drinks, put something in the hat, get a CD to take home.. every pint you buy helps ensure the survival of the music you love. It’s a win-win deal.

Eddie Myer