The Column: Eddie Myer – The Recording Angel

In jazz history, the period hailed as the Golden Era is rather a moveable feast – Dixieland purists and similar mouldy figs may insist that the title cannot be accorded any later than the onset of the Great Depression, William P Gottlieb appropriated it for his riveting collection of photographs from the 1930s and 1940s, but for many today it’s the post-Parker years of the 1950s and 1960s that define the seminal phase of the music’s development. Albums such as Thelonious Monk’s Genius of Modern Music, Miles Davis’ Bags Groove, and his Prestige series Walkin’/Cookin’/Relaxin’/Steamin’, Sonny Rollins’ Saxophone Colossus, Horace Silver’s Jazz Messengers, Art Blakey’s Moanin’ and Cannonball Adderley’s Somethin’ Else shaped the way that the bop experiments of the 40s became the new hip mainstream – to be followed by a bifurcated pathway as players gravitated towards the funk epitomised by Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder, or set off into uncharted waters, returning with such glorious discoveries as Wayne Shorter’s Speak No Evil, Cecil Taylor’s Conquistador, Eric Dolphy’s Out To Lunch, and the universally acknowledged masterpiece that is Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. All the above works taken together, diverse as they are, could form the cornerstone of a good, comprehensive modern jazz collection – and remarkably all were recorded by the same man, in suburban New Jersey, in his own studio originally located in the living room of his parent’s house. Rudy Van Gelder passed away this week at the age of 93, one of the lone survivors from a mythical age when musical giants walked the earth, leaving behind him a discography that runs into the thousands and defines the sound of a crucial era of the music’s history. As the number one choice of recording technician for both Blue Note and Prestige records he played a pivotal role in defining the sound of those labels at the time when they themselves were defining the sound of jazz, and later work for Impulse! and Verve was equally trendsetting; his later work for CTI was as broadly influential, if not as well-loved by the critics. He oversaw every aspect of the recording process, meticulously positioning each microphone with white-gloved hands, tracking and mixing everything himself and even cutting the final LP masters on his own lathes. By today’s standards, his methods were very simple – many of his seminal recordings were made directly to two-track tape with a minimum of signal processing – yet his sound is instantly recognisable, even as fans and critics struggle to define it exactly – ‘naturalism’ and ‘warmth’ are adjectives often employed. He excelled in using scientifically precise microphone placement to capture both the individual tone of the player and the collective sound of the group, so that his recordings have a sense of space and clarity, with each instrument clearly audible in its proper place, and you’re given the illusion of being in the room, sat right in front of the band. This was a perfect match for the new, small-group sound of the time – the era abounded with distinct, individual voices on horns and piano, while new innovations in drum kits and cymbals gave drummers the opportunity to play a greater role in shaping dynamics and timbre, and improved microphone and equalisation technology allowed bassists to be heard clearly enough to start exploring subtler melodic and rhythmic possibilities than in the ‘grab it and whack it’ days of Wellman Braud. A modest man in his rare interviews, Van Gelder would be the first to avow that the primary creative genius resided with the musicians, but his ability to capture the music’s intent surely helped to shape it’s successful realisation.

Jazz music’s existence runs nearly exactly contemporaneously with the existence of recorded music, and has been shaped by the technology, as it has helped to shape it. To those far from the epicentres in Storyville, 52nd Street or Lenox Avenue, jazz was spread to its devotees via the medium of rare, highly-prized records, especially in the post-war UK, as the Musicians’ Union placed restrictions on US players touring. Many jazz musicians insist that records never capture more than a snapshot of their art – just the sound of one day in their endless musical progression – but to the fans it’s often the records that are the defining documents, and when the players are no more it is the recordings that constitute the legacy; oral memories of legendary gigs are simply tantalising if you weren’t there.

In the 1930s and 1940s the cream of the sound engineers aspired to work with symphony orchestras or in movies; jazz was still widely seen as a throwaway medium unworthy of the best equipment, and magnetic tape recording didn’t become common ’til the early 1950s. Charlie Parker’s brilliant Savoy and Dial sides have an excitement and immediacy that transcends that hiss and crackle of the shellac 78 played with an iron needle; the genius is clearly audible, but the drums and bass are often not, and the sound often manages to seem shrill and muffled at the same time, so that protracted listening can become something of a chore for those who aren’t aspiring players themselves. Rudy Van Gelder set a benchmark for high fidelity in jazz recording, and a standard of care and respect for the musician’s intent (though Mingus refused to use him, claiming ‘he ruined my bass sound’), and much of the jazz we hear today bears traces of his subtle, indirect influence. In his later years, he was occupied in an extensive programme of re-mastering his back catalogue for digital re-release – interestingly, given the importance of the Blue Note LP as artefacts in the cult of analogue, Van Gelder himself had no sentimental attachment to vinyl as a medium, declaring “The biggest distorter is the LP itself. I’ve made thousands of LP masters. I used to make 17 a day, with two lathes going simultaneously, and I’m glad to see the LP go. As far as I’m concerned, good riddance. It was a constant battle to try to make that music sound the way it should. It was never any good. And if people don’t like what they hear in digital, they should blame the engineer who did it. Blame the mastering house. Blame the mixing engineer. That’s why some digital recordings sound terrible, and I’m not denying that they do, but don’t blame the medium”. He also continued to be involved in recording new artists, notably Christian Scott’s groundbreaking 2010 release Jenacide. There’s several further articles to be written about the relationship between the recording and the performance, how jazz musicians and fans alike interact with the record industry, and how technology and music aid, abet and afflict each other; let’s leave those for another time and salute the achievements of the backroom boy from Hackensack.

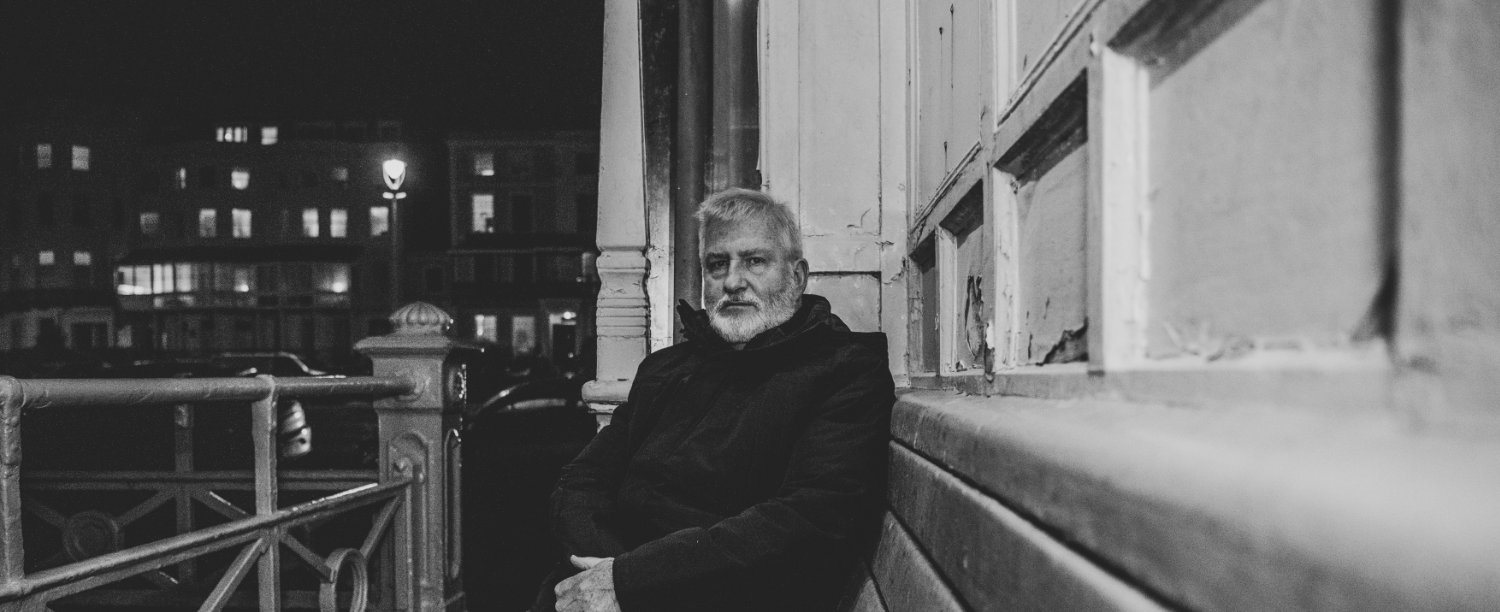

Eddie Myer