Improv Column: Terry Seabrook’s Jazz Tip of the Month No. 6

Pianist Terry Seabrook’s Jazz Tip of the Month No. 6

Encoding The Chord Changes With Some Colour

Here’s a nice little idea to help the amateur improviser find the scales to use over the “changes” in a chord sequence. (“Changes” is a word meaning the chords, as they “change” from one to the next)

The technique outlined here was used by a student of mine, and although he assured me he had seen it before, I hadn’t and it struck me as a good idea for the beginning to intermediate improviser.

In chord sequences there are always strings of chords which belong to a key. That’s the way functional or tonal harmony works. (Some music may use harmony which is non-functional or atonal in sections or for a whole piece, in which case the ideas here won’t apply).

Some songs can stay in a key centre for a long time eg Blue Moon or Mambo Inn stay in F major for the entire A section:

BLUE MOON (A1):

|Fmaj7 / Dm7 / |Gm7 / C7 / |Fmaj7 / Dm7 / |Gm7 / C7 / |

|Am7 / Dm7 / |Gm7 / C7 / |Fmaj7 / Dm7 / |Gm7 / C7 / |

MAMBO INN: (A1):

|Gm7 / C7 / |Fmaj7 / Dm7 / |Gm7 / C7 / |Fmaj7 / Dm7 / |

|Gm7 / C7 / |Am7 / Dm7 / |Gm7 / C7 / |Fmaj7 / Dm7 / |

In the examples above the harmony just repeats turnaround* type chord sequences in the home or tonic key and the chords given here are all from the scale of F major. For this reason, F major is a perfectly good starting point for improvising across the chord sequence.

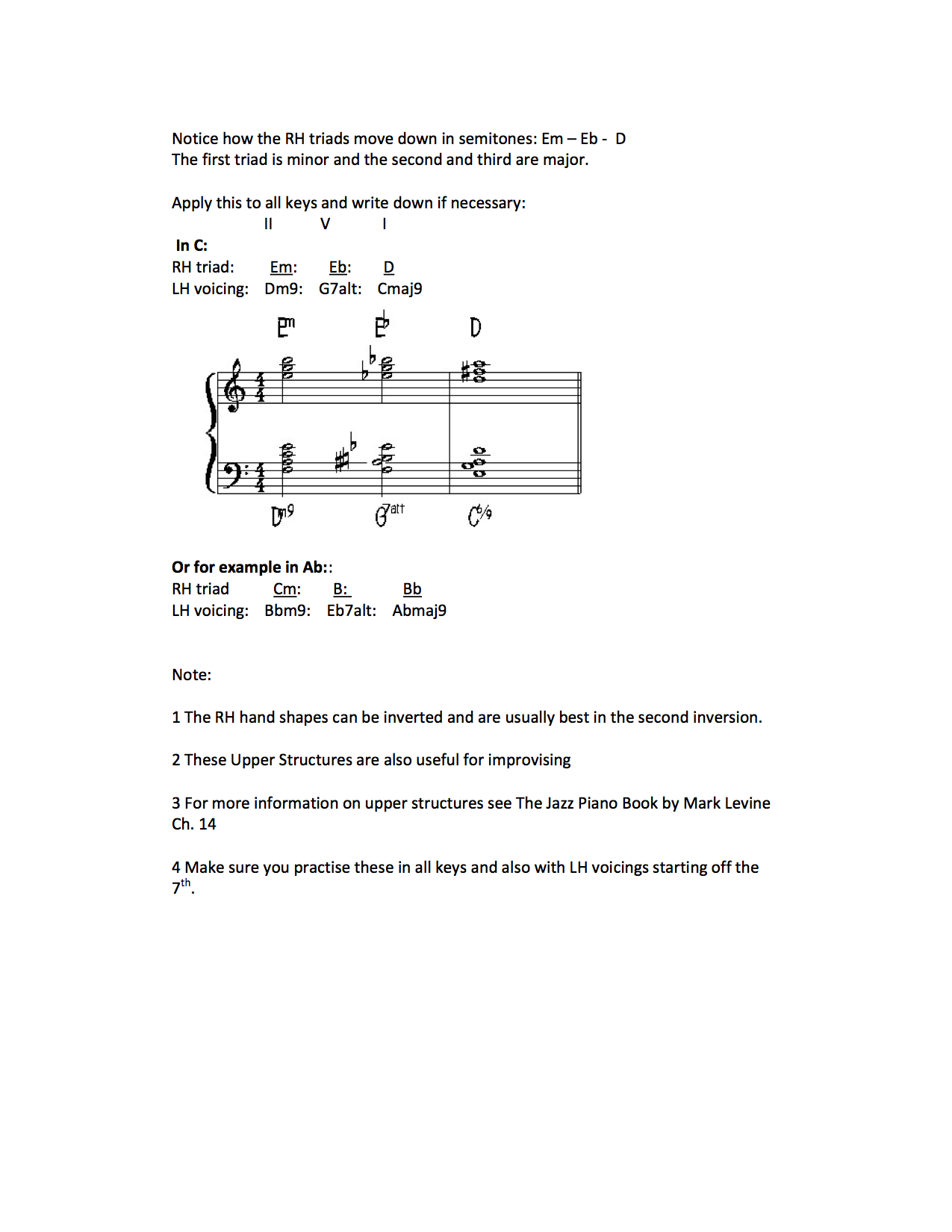

I often suggest to students that they should write the scale over a set of changes which share the same parent scale system. The most basic example would be a II –V- I sequence in C ie: Dm7 -G7- Cmaj7. Although you can describe the scales as D Dorian, G Mixolydian & C Ionian, these three “modes” are all actually versions of C major. Similarly in the 2 song examples above you could write in F major across the whole 8 bars.

However, when you get skilful at spotting groups of chords sharing the same scale you won’t need to write them in. Sometimes, however, even professionals indicate the scales required in a piece either because the sound desired is specific and possibly not the normal choice. Other times it may be put in just as an aide in a difficult passage.

Bill Evans actually wrote out the 5 modes for his fellow musicians to use on the piece Flamenco Sketches on the classic 1959 recording by Miles Davis, Kind of Blue. This is clear from a photograph from the session of the music on Cannonball Adderley’s music stand:

Anyway, instead of just writing the scale in, you could use some colour to help you see the scales (or key centres as they might often be) as in the following example. This is the first 8 bars of Afternoon in Paris by John Lewis which is basically a II-V- I in three keys.

Doing this often demonstrates the actual small number of key centres in a single piece; ie: you won’t need a whole kaleidoscope of colours. Relative minors can use the same or a slightly different colour – it’s up to you. There is no particular system here behind the colours used for each key unless you have synesthesia. Be as artistic as you like.

So all off to WHSmith’s for a pack of felt tip pens.

Mention my name to the sales assistant as I’m on a small commission.

Who said there ain’t no money in jazz?

*A turnaround often appears at the end of the song and usually resolves to the tonic (I). But if you want to repeat back to the top of the chorus, a turnaround is a little sequence to take you there – often back to the tonic at the start. In F major it would be:

|Fmaj7 / Dm7 / | Gm7 / C7 / ||Fmaj7 etc.

In general it would be:

|I / VI / | II / V / || I etc.

Terry Seabrook performs every Monday evening at The Snowdrop in Lewes.