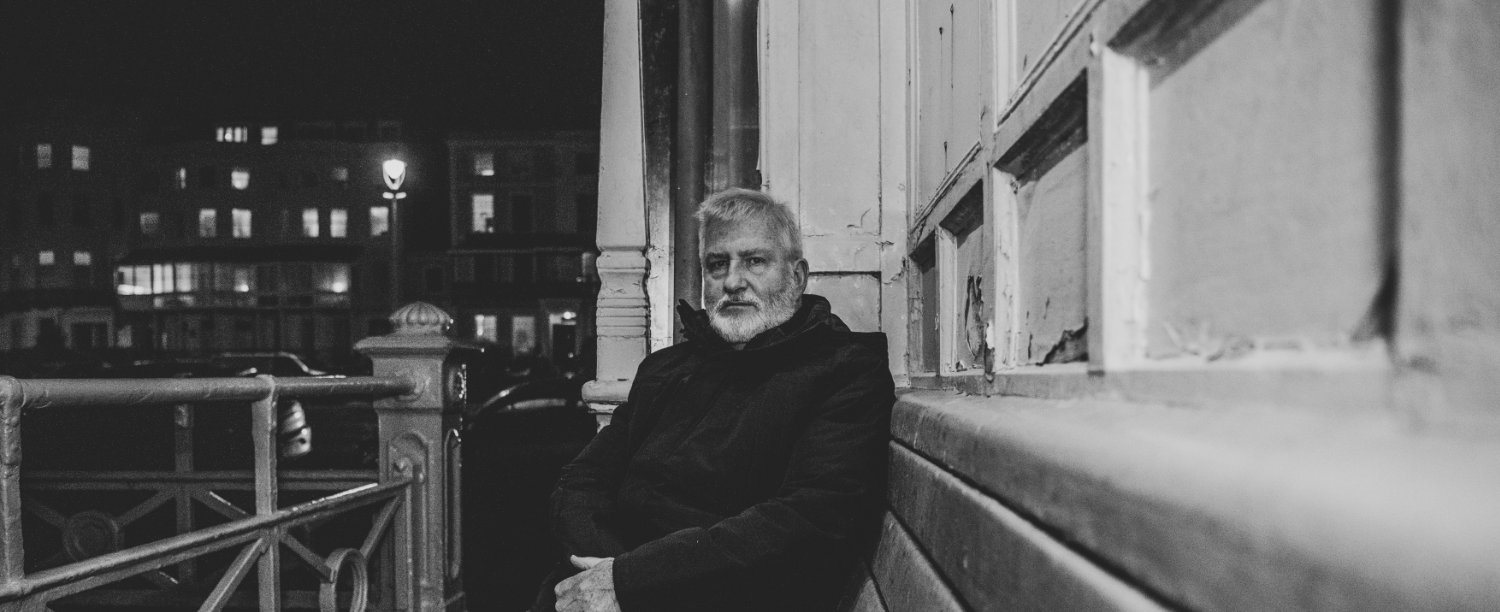

The Column: Eddie Myer – Ars Longa, Vita Brevis

The first ever jazz record is usually reckoned to be the Original Dixieland Jazz Band’s shellac 78 release of Livery Stable Blues on the charmingly named Victor Talking Machine Company. The release date was March 7, 1917, probably described by their A&R man as ‘not a great date for a release’ – a bit under a century ago. As there are an estimated 53,364 centenarians still at large in the USA alone, we can say that the entire history of jazz and related musics spans a single lifetime.

The pace of evolution has been dizzying; you can make a passable analogy with the symphonic music tradition and say jazz has gone from primitive to baroque to classical to modernist to post-modern to neo-classical with such speed that some players have been long-lived enough to play all the above styles in the course of a single career. The bassist Milt Hinton’s cv spans this history of musical and technological changes from gut-string slapping with Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong to hi-fi digital recordings with Branford Marsalis, while Herbie Hancock’s protean career has seen him make a stab at all kinds of new things from bop to free to funk to electro to hip-hop and back again in a kind of time-loop.

The sad news that Sonny Rollins has had to cancel his annual London appearance on health grounds makes us realise how fragile are the links that connect us to the past. The black-and-white, 78rpm, racially segregated, war-torn world of the be-boppers seems so far away from contemporary life, and the pace of musical change has been so fast, that it’s a bit of a shock to realise that Roy Haynes, still alive and gigging this year, was also once in Parker’s band to witness the birth of modernism. The be-bop vocabulary is now so codified and curated by the most respected echelons of musical academia, that it’s hard to credit how recently it was brought into being, within the working lifetime of a drummer, out of nothing more than talent, chutzpah and some well-thumbed Stravinsky scores: no Berklee study programmes were available to these hard-working dance band musicians as they set about re-writing the rules . Equally, post-war British players trying to keep up with developments had to teach themselves, by ear, from whatever scratchy shellac discs they could get their austerity-pinched hands on. Jazz musicians are characteristically hungry to learn and progress, and it’s this appetite that has driven the relentless pace of change.

A sadder side to this picture is revealed when you start account for the thinness in the ranks of survivors of these generations of innovators. If the jazz discographies are long, so are the jazz obituaries. While jazz musicians have historically shown an appetite for progress and innovation, they’ve also been prey to darker and more destructive appetites, and the blue-print for the ‘rock-and-roll lifestyle’ was drawn up in the jazz age of the 1920s or before. The sad story of Parker, dying ‘of everything’ at the age of 34 is well known, as is the pernicious effect that his hard-partying reputation had on subsequent generations of imitators. Equally, Billie Holiday’s life story was spun into the destructively enduring myth of the tragic, doomed heroine, with Amy Winehouse most notable among its recent victims. But jazz musicians in the old days were vulnerable to a range of afflictions peculiar to the way they had to live; a little research through my Penguin guide shows that most ‘classic era’ jazz players were lucky if they made it past 60. As well as their own self-induced drink and drug problems, they were picked off by communicable diseases (Jimmy Blanton and Charlie Christian both lost to TB just as they were changing the course of the music), heart attacks caused by the general stress of non-stop late-night gigging and touring with the concomitant terrible diet (Wes Montgomery, Cannonball Adderly, Grant Green) and mental health problems exacerbated in many cases by racism, poverty and frustration (Bud Powell, Monk, Butch Warren). A significant amount of talent was also lost on the roads (Richie Powell, Clifford Brown, Doug Watkins); then , as now, jazz musicians had to travel constantly to make a living, and endless car journeys could be pretty risky in the days before ABS, airbags or even seatbelts were standard equipment. A lesser-known risk, certainly one that nobody at the time would have counted, reveals itself when you notice the amount of 1950s and 1960s horn players who died early of emphysema – night after night of hard blowing in smoky night-clubs took the inevitable toll.

Nowadays, the situation is much improved on almost all counts. Jazz now has a place on the tranquil pastures of academia, and the security of academic tenures, the improved safety features of modern cars, the smoking ban and (in the UK) free universal healthcare have all significantly improved the jazz musician’s life expectancy. The Musician’s Union, the PRS and the Musician’s Benevolent Fund all provide assistance to players who may find their health failing just as their gigs dry up in their uninsured old age. And in the meantime, we can all benefit by going to see performances by the originators and creators of the music we love whenever we get the chance…These guys are repositories of the entire history of the music, and at the risk of sounding ghoulish, you have to realize they won’t be around for ever.

Eddie Myer