The Column: Eddie Myer – Emperor’s New Clothes

I recently had the good fortune to participate in a recording session with Mark Edwards, noted keyboard supremo, studio whiz and mysterious mastermind behind the uncategorisable and irrepressible Cloggz project. During the downtime he shared his reminiscences of playing with the Tommy Chase Quartet. It reminded me that, although you don’t hear so much about his high-powered, hard-swinging outfit these days, Mr Chase deserves a chapter of his own in the history of British jazz-and-related-musics.

This column has previously explored, albeit superficially, the changing fortunes of jazz in that mysterious period of the mid 80s when it suddenly found itself fashionable again. Perhaps punk and its offshoots had come to seem like rather dreary old hat, and the wider public discovered an appetite for a slicker, more glamorous vision of the zeitgeist that found its musical evocation through embracing such previously shunned cultural tropes as saxophones, conga drums and extended chords played on the fender rhodes. In the more commercial arena, the public’s engagement with jazz wasn’t much deeper than that – artists like Sade, Curiosity Killed the Cat et al employed jazzy devices as a sort of garnish on what remained basically pop-soul. One imagines the older, radically committed jazz generation balking at the dilution of their musical and political identities, but a younger crowd of players took advantage of the newly prevailing winds to launch careers that have lasted in some cases to this day – Courtney Pine is perhaps the best known example of someone who’s appeared on Top of the Pops and emerged with his jazz credentials untarnished.

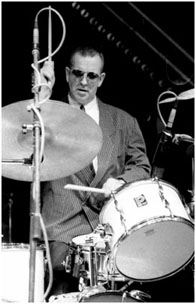

Tommy Chase rode this wave, but also stood distinct from it, in that his quartet dealt exclusively in hard bop of the old school, complete with upright bass, acoustic piano, and a total dedication to swing. His belief in the music was unshakeable; he saw no reason why a 1950s style jazz quartet couldn’t be as commercially viable a part of the contemporary music scene as anything else; and for a while, he got a lot of people to agree with him, partly it seems through sheer force of character. The band appeared in the press, played sell-out gigs in regular, non-jazz venues around the country, made records with hot young producers and even got some of those records into the charts. What’s all the more remarkable is that they did it without diluting the leader’s maniacally unswerving dedication to the artistic verities codified by Blue Note Records thirty years previously. Some of our most celebrated current torchbearers of the tradition passed through the band – notables such as Alan Barnes and Andy Cleyndert. It didn’t seem to be stretching a point too far to see a lineage stretching back to the Jazz Couriers of 60s Soho, or even across the Atlantic to the Jazz Messengers and the irascible Mr Blakey himself.

Tommy was undoubtedly assisted by the wider public’s continuing willingness to buy into the Mod aesthetic in its various forms. 1986 was the year of an ambitious, swinging-London movie adaptation of Colin McInnes’ seminal youth-culture novel, Absolute Beginners – the book’s un-named protagonist is a streetwise London teen who combines a disaffected attitude and a hustler’s irreverent ambition with a love of Italian suits and the Modern Jazz Quartet. The fact that he lives in a Notting Hill of cheap rents and impoverished immigrants makes him seem today even more like a creature from a fabulous distant past, but the cultural gap was narrower then, and figures as diverse and influential as David Bowie and the Modfather himself, Paul Weller, adopted aspects of the cultural package that the book and its spectacularly unsuccessful film adaptation tried to embody.

Presentation was everything; Tommy was not only evangelical about his (at the time still-unreissued) 60s Blue Note platters, but about the dictates of Mod fashion, which led to him prescribing every aspect of his musicians’ appearance from socks to haircuts. Not only did the band rehearse with military regularity – they rehearsed in suits and ties. This may seem a bit much today – Mr Chase by all accounts was an extremely difficult man to deal with, whose emulation of the methods and self-belief of the Jazz Greats extended to include some of their most challenging character traits. But on a professional level it was pure showmanship; and it seems an inescapable fact that this kind of showmanship is rather absent from the scene today, and the scene seems the poorer for it. Today’s players often opt for a non-committal jeans-and-suit-jacket look, like academics on sabbatical (which to an extent is what many of them are), or at worst embody the unfortunate paradigm of unkempt men in wrinkled casualwear hunched morosely over their instruments which has done so much to alienate the uncommitted public from the music. This is in stark contrast to previous generations – Miles in particular believed that a radical musical vision was best presented in snazzy threads. We’re not suggesting that a wholesale return to the Dark Magus’ shell-suit-and-hair-weave look of later years would be an effective cure; but a re-examination of the legacy of the Tommy Chase Quartet is surely overdue – both for the music itself, and for it’s leader’s belief that jazz had as much right to a place in the mainstream as anything else.

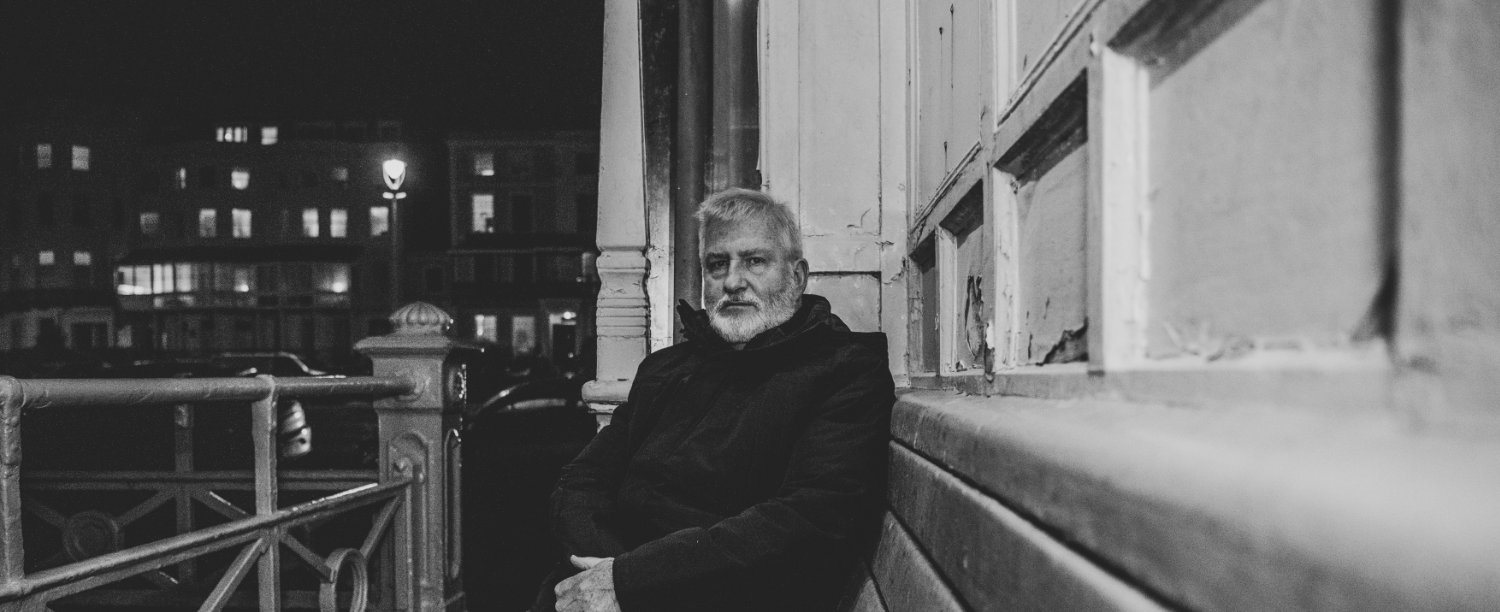

Eddie Myer

[Photo of Tommy Chase by Brian O’Connor]