The Column: Eddie Myer – What’s In A Name?

Last Friday I managed to get myself along to see much-favoured youngbloods Empirical playing at the Pavilion Theatre to an appreciative crowd. It was a rare chance to see something from the current forefront of jazz-and-related-musics on our doorstep, and I was pleased not to recognise any local players among the audience, as everyone except me evidently had their own high-paying Friday night gigs to attend to. The music was outstanding and I was struck by the way the band shared announcing duties, each member taking his turn to come up to the mic and provide, in that particularly English style of self-deprecating affability, a link between the songs and between the band and the audience. This emphasised that Empirical are that relative rarity in jazz, a band with a stable line-up and a collective title. When you consider that collective improvisation is an essential component of jazz and one that sets it apart from other musical forms, it’s surprising that ensembles of players don’t have the same kind of genre-defining role as they do in, say, rock music. Jazz history is told in terms of an apostolic succession of supremely talented individuals, lone geniuses who re-wrote the rules and moved the music forward in a relentless pursuit of personal self-expression, figures so iconic that they can be referred to simply by their nicknames, which can be invoked to validate or refute another player’s worth. As jazz has moved away from the increasingly hostile shores of the commercial music business into the more temperate climes of academia, the idea of jazz as a canonical body of knowledge that is transferred according to an approved hierarchy has gained credence. Are we overlooking something?

The study of context is always illuminating. The early jazz acts, like the vaudevillians that preceded them and the rock-and-rollers who succeeded them in the wider public’s favour, sought safety in numbers and presented themselves before that public in groups. The names give a flavour of these early exercises in musical image creation; The Original Creole Jazz Band, the Baton Rouge Syncopators, and The New Orleans Rhythm Masters were all helping to shape this new music into a recognisable brand, while names like The Tuxedo Band and The High Society Swingers tried to give the brand a flavour of the high life. “Hot” was a good buzzword for the roaring 20s, with founding father Jelly Roll Morton appearing with his Red Hot Peppers and Louis Armstrong emerging from a series of Hot Fives and Hot Sevens. The trend continued into jazz’s commercial heydays of the 30s and 40s, but as jazz’s commercial and artistic status solidified, record companies, booking agents and managers started discovering the power of the star bandleader or soloist. The career of Artie Shaw furnishes a particularly striking example of the way that a bandleader’s public image could be groomed and manipulated in the same way that a movie star’s could be; Artie himself invited such comparisons by helpfully dating as many actual movie stars as he could. The public started learning the names, not just of the bandleaders and featured vocalists, but of star soloists like Johnny Hodges and Coleman Hawkins, which meant there was now a commercial imperative at work putting their names on the record sleeves and concert posters. As jazz moved form being big band dance music into its post-bebop era of small groups and intellectual respectability, a new generation of aficionados emerged who had learnt to scan the record credits for their favourite names before buying. The communal ethos of Dixieland was replaced by a form which emphasised a succession of featured solos, usually taken in order of importance and ending with the bass player. Labels like Blue Note and Prestige developed marketing strategies accordingly, developing pools of trusted crack players and putting everyone’s name, even the bassists, on the front cover, and developing new stars by pairing them with established players so as to indicate a clear succession. While Art Blakey and Horace Silver carried on the tradition of presenting the public with a band, they were going against the tide. “Groups” played rock music – jazz was marketed as collections of star soloists fronting star sidemen, or genius auteurs such as Miles Davis whose name was enough to sell records even if he hadn’t composed the bulk of the material or played most of the solos.

Jazz today is still heavily dependent on the big name to sell records and concert tickets. However, there’s been a noticeable trend lately towards a return to the group concept, especially here in the UK. Precedent was set by mighty 80s acts the Jazz Warriors and Loose Tubes, and as jazz continues to search for an identity (and a commercially viable one) there seems to be a growing feeling that the frontman-plus-sidemen model can often end up sounding like less than the sum of its parts, while a group can provide a stronger identity that allows the music to thrive, and makes it easier to sell to a younger audience. The changing names tell a story of how jazz has evolved, from John Chilton’s Feetwarmers to weighty appellations like Phronesis, Triptych and Kairos 4tet. What remains unchanged is that jazz has always been a communal music; in its highest development, it’s a form of spontaneous group composition in which each player’s personality remains recognisable, yet is subsumed within the unity of the performance. It’s what makes the music unique.

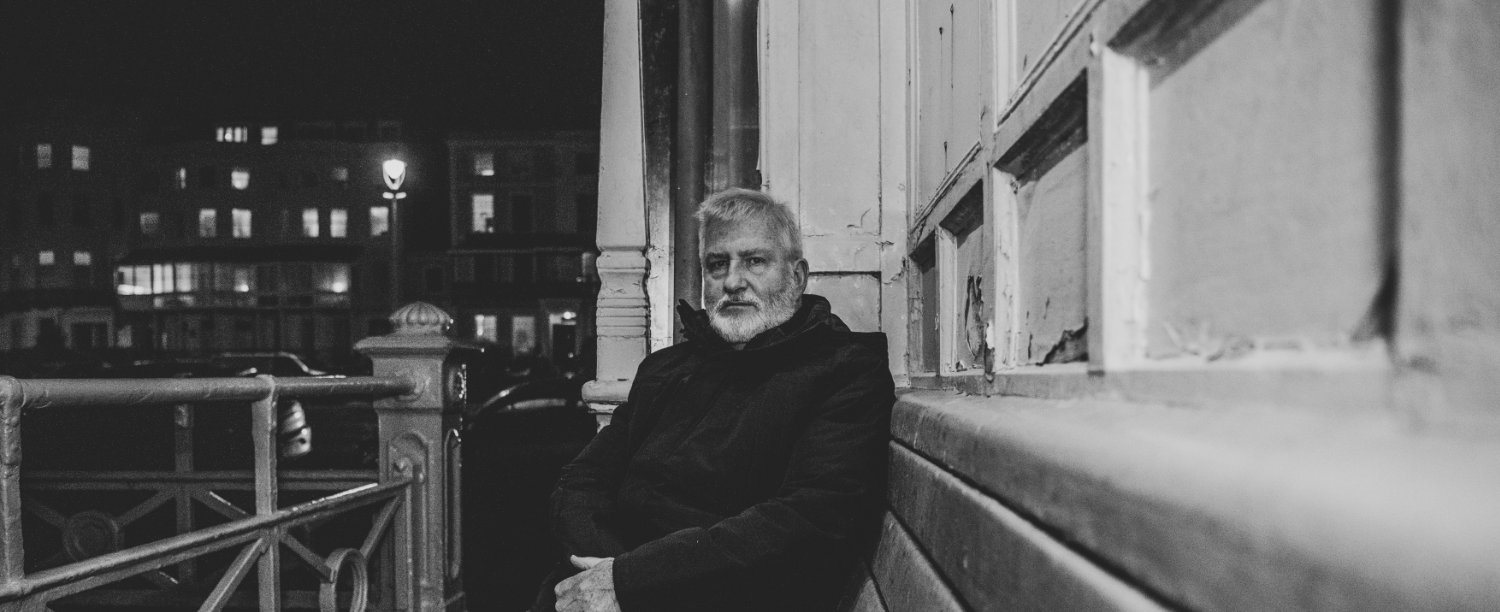

Eddie Myer