Bitches Brew Discussion

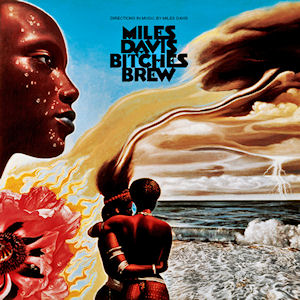

Following on from Eddie Myer’s column in the May issue (which you can read here) concerning Miles Davis’ classic Bitches Brew album, we print responses from readers Milo Fell and Ken Edwards followed by a response from Eddie Myer.

Milo Fell writes…

I am writing to take issue with Eddie Myer's latest column, and in particular his comments on Miles Davis' Bitches Brew album. I usually find Eddie's column entertaining, interesting and thought provoking, though on this occasion I feel he's fallen well below his usual standards and has produced a nonsensical, confused, inaccurate rewriting of musical history.

Bitches Brew is regarded by many as one of the greatest recordings of Miles Davis' career, a huge success, both artistically and commercially (in jazz terms). Eddie wonders how the record "somehow became a massive seller" despite it's "ominous and murky ramblings", the answer is that it did so well because it is nothing short of a masterpiece, utterly original and completely in tune with the zeitgeist of it's time. I know it's not everyones cup of tea, but to question it's significance in the music is a red rag to bull for a fanatical zealot like me.

Eddie claims that Bitches Brew was "totally out of step with the sound of the subsequently emerging generation of fusion players". In the first place this makes no sense – how can something be out of step with something else that hasn't happened yet? Secondly this is just plain wrong – the influence of Bitches Brew can be heard in any number of early fusion records in the years immediately following it's release (1970-72), such as those by Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi band, Weather Report's first couple of releases and many others. It's hard to see the influence of King Oliver on the music of today, unless you put the effort in to join the dots.

Eddie's account of the recording sessions is also highly dubious, saying that Miles "gathered a team of younger players into the studio, sketched out the vaguest of musical goals, and set the tapes rolling". According to the accounts in Ian Carr's biography, and elsewhere, Miles's involvement was far greater, entirely reworking the two compositions that weren't his own, exerting what was described as a "telepathic control" over the ensemble, as well as giving verbal instructions (audible on the record at one point), but most of all directing the band through his astounding playing. Also three of the tracks had been broken in by being played live for several months, and rehearsals were conducted before the sessions. The beauty comes from the ensemble acting as a foil for Miles, hanging on his every note, as Carr says "the music is created by the ebb and flow of the improvising ensemble under the spell of Miles's phenomenal trumpet playing".

Eddie's column flits between Bitches Brew and On the Corner, a very different, and much less successful, record made three years after, and arguably (according to Carr again) from an entirely different phase of Miles's career. Eddie make little distinction between the two, not identifying which record certain quotes refer to and referring to both as part of "Miles's 70s explorations".

These opinions are supported by scathing quotes from Rolling Stone and Donald Fagin, unbalanced with any positive quotes and no mention of the acclaim the record received at the time or the Grammy it won. As Leonard Feather said, the idea that he was trying to make a funk record is "dangerously over-simplistic…..He is creating a new and more complex form, drawing from the avant-garde, atonalism, modality, rock, jazz and the universe. It has no name but some listeners have called it 'Space Music' ".

I could go on more about the problems I have with the column (the analysis of On The Corner, the idea that Bitches Brew is only seen as influential "on the strength of it's personnel", the notion that Bill Laswell and Thom Yorke's approval has led to a "rehabilitation" of the music), but I'll end with a quote from Miles himself: "Critics like to pigeonhole everybody, put you in a certain place in their heads so they can get to you. They don't like a lot of changing because that makes them have to work to understand what you're doing. When I started changing so fast like that, a lot of critics put me down because they didn't understand what I was doing." Eddie Myer needs to work harder.

Milo Fell

Ken Edwards writes…

I usually enjoy Eddie Myer’s column and I did again this month but I have to take issue with some things he asserted.

I came to the music that is usually identified as “jazz” via Miles Davis, and more specifically via Bitches Brew – as an 18-year-old student infatuated with Jimi Hendrix, Cream, the Beatles, the Stones…. I thought the music was so mysterious, so visceral, yet remote as a distant planet. I loved it. Only then did I investigate Miles’ back catalogue, and also along the way discovered John Coltrane, and even started listening to Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk, although that music didn’t speak as directly to what I thought of as my generation.

I have to say that my excitement at finally witnessing Miles live – I think it was around 1972-3 – was tempered slightly by his not playing the trumpet that much – he seemed to be into a somewhat cruddy sounding keyboard half the time – and also because the slinky, funky rhythms had been rather submerged under some brash rock drumming.

But to say that his subsequent records were “increasingly peculiar-sounding” is really rather silly, and to compare them unfavourably to Weather Report astonishes me. That band’s first couple of records were great, but they developed an increasingly slick and empty sound: the virtuoso noodling that so many rock fans complain about became increasingly evident and started to turn me off.

And I like Steely Dan’s gleaming pop arrangements with jazz tonality and jazz levels of musicianship (“super-tight studio perfectionism” gets it exactly), but there is no room to breathe in their music, and Donald Fagen doesn’t hold a candle to Miles, I’m sorry.

So now we’re in the post-Marsalis era and “jazz” has become another marketing niche. The music is played increasingly by conservatory-educated musicians who have learned all the moves at college, know the rules and mostly abide by them. The material is of course largely The Great American Songbook – i.e. songs written before about 1962. I regularly go to the Hastings Jazz Club, where the visiting musicians are without exception first-class. But you have to accept little that is truly new will happen. The head will be played. The band leader will take a solo. The other front-line player will take a solo. The bass player may or may not solo. The leader will trade fours or eights with the drummer. The head will be returned to. Then it will happen all over again. And the audience? I have just reached state pension age yet I am usually one of the younger ones there. Hmmm.

Far from “lumbering jazz with the onerous burden of having to constantly assert its forward-looking progressive credentials”, my take on Coltrane and Ornette and the others of their kind is that their restlessness, their yearning to make it new again was exciting in ways it’s hard to find today. Sometimes I do get excited again. For example, Henry Threadgill’s current band, Zooid, seems to me to capture the thrill of heading into the unknown while keeping an unbearably urgent pulse in the air. It’s telling that in a recent interview I heard online Threadgill says he believes the term “jazz” is meaningless and has been for many years. Funny, Miles also said that back in the day.

I mean, where did that word come from? Not from the musicians. It was originally a derogatory term applied by others to a despised music that had no name.

The music of the present that will persist into the future presently has no name, I believe, even if “jazz” is one of the influences.

I have yet to catch up with the Don Cheadle Miles biopic, but I will do so, it looks promising.

Ken Edwards

Eddie Myer responds…

Gentlemen,

Thanks for taking the time to read my column, and for sharing your responses. Last week’s investigation into Miles’ enigmatic 70s period has excited even more controversy than my feature touching on Gilad Atzmon’s views on Palestine, which takes some doing. However, it seems to me that both correspondents have misread my intentions to a degree.

My aim was, if not to praise Miles (plenty of work has already been done on that front, by far greater writers than me) then certainly not to bury him either, but to draw attention to some of the unusual aspects of the fascinating period that immediately preceded the setting for the recent Don Cheadle pic. “Bitches Brew” is often cited as the album that introduced this era, and as the fons et origen of what became known as jazz-rock or fusion, on the strength of (but not, I hasten to add, exclusively because of) it’s cast list which included many of the 70s’ biggest stars. To my ears it sounds more as though it exists in a genre of it’s own; I think it’s both grammatically and factually justifiable to say that Miles’ innovations were out of step with the subsequent directions pursued by the generation of players introduced to the public on “Brew” – it seems to me that he went one way, and Messrs Hancock, Corea, Cobham, White, Moreira, McLaughlin et al went another. But perhaps I could have averted some of Mr Fell’s wrath had I stated more plainly that I see this as a positive endorsement, not a negative criticism. Personally, I like “Bitches Brew” very much, and “Live-Evil”, and “On The Corner” is another favourite – I prefer ominous, murky ramblings over polished studio precision any day – and I fully sympathise with Mr Edwards’ assessment of how the magic that he hears in the first two Weather Report albums became dissipated over their later, more commercially successful recordings. The Penguin Jazz Guide critics Richard Cook and Brian Morton describe ‘Brew’ as “much less beautiful than ‘In A Silent Way’, and far more unremittingly abstract … one of the most remarkable creative statements of the last half-century… but also profoundly flawed, a gigantic torso of burstingly noisy music that absolutely refuses to resolve itself under any recognised guise” which I think captures better than I could the way that both that album, as well as the many exploratory (or ‘peculiar-sounding’) records that followed, continue to delight and inspire some, and perplex others more accustomed to the reassuringly timeless sound world of ‘Kind Of Blue’ or the disciplined but airless flamboyance of Jazz-Fusion as it later developed.

Miles’ own working methods, and his inner goals, were to an extent ultimately and perhaps deliberately shrouded in mystery by the man himself. It’s impossible to second-guess a genius at a distance of 50 years. He was, however, overt in his intention to reach out beyond the shrinking, increasingly specialised jazz audience, and so I think it’s entirely appropriate to discuss his work in terms of how it was rediscovered and re-evaluated outside the jazz world. As Mr Edwards points out in his closing remarks (which surely contain the seed of another column, coming your way soon) the tradition needs to innovate in order to survive. Acknowledging the genius of the greats is important, and I’m happy to set the record straight and say that I can join you both in stating unequivocally that the music Miles made in the 70s, from “Bitches Brew” onwards, includes some of his (or anyone elses’) most important and influential work. But I make no apology for daring to call his judgement into question – an excessively reverential attitude towards the legacy is ultimately stifling to progression, and is the very thing that Miles was surely trying to overcome.

Eddie Myer