Improv Column: Rhythm Changes Basics by Wayne McConnell

Pianist Wayne McConnell looks at rhythm changes.

Rhythm Changes Basics

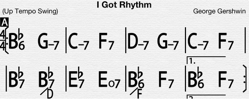

Rhythm changes represents a set of chord changes over an AABA form that resemble the chord changes to Gershwin’s ‘I Got Rhythm’. Many people find it difficult to improvise over these chords. There are many ways of playing through a Rhythm Changes with different/alternative chord changes and concepts. We are going to look at a few different ways to approach playing Rhythm Changes.

First, we need to know what the chords are. I recommend going through some of the similar steps that I’ve mentioned previously; singing the root movements, making sure you can play simple R, 3 7 voicings (even if you don’t play piano), making sure you have nice sounding voicings for the chords (if you are a chord player). I’m going to break down the chords into their relevant AABA sections so we can see all of the alternative changes. In the most basic format, the chord changes to the A section are:

A-Section

The first line can be described as : I, VI, II, V, III, VI, II, V

The second line is often described as the ‘release: this is because the chromatic run up in the bass creates tension on the run up to chord I. There is an alternative to line two:

The Bb, Bb7/D is replaced with a II-V going to Eb7. You can also replace the Eb7 with Ebmaj7. The Bb6/F in the first example (3rd bar) is replaced with the III chord. This is also a very common substitution.

A very common way of getting through the first 8 bars is to use diminished chords that create a chromatic runup e.g:

You can of course substitute all of the dominant chords in some way. Adding alterations and tritone substitutions work well. In the following example I have shown where you can alter the dominant chords by turning them into 7alt chords:

You don’t have to keep them all as ‘altered chords’ you can use b9 (for diminished sounds) and tritone substitution.

Another concept you can use on the A section of a Rhythm Changes is to move the other way. Rather than cramming loads of chords in, think of the whole 8 bars as being some kind of Bb sound (major, minor or dom):

This will create an open/modal sound for you to explore. Although this looks like the simplest option, in order to make this work you really have to be able to play all of the alternative changes before.

Bridge

Usually the Bridge of a Rhythm Changes is simply III, VI, II, V two bars of each and all of them turned into dominant 7th chords. I.e.:

There are however, many variations that you can play in the Bridge. Some of them are substitutions that you can use without informing the bassist and others that would require you to tell the bassist. We will look at a few of them now.

II-Sub

This first example of alternative changes in the Bridge shows that you can precede each V chord with it’s II chord turning them into II-V movements.

Tritone Subs

Here we are simply replacing the dominant chords with the tritone substitution. Not altering the first chord to (D7) to Ab7 gives us a nice chromatic descending sequence.

Some tunes are specifically written with different changes and substitutions in the Bridge. A really fun one is Eternal Triangle by Sonny Stitt.

There are many other things you can do on a Rhythm Changes but lets look at soloing techniques over the chords.

Soloing Over a Rhythm Changes

The reason why Rhythm Changes is often seen as a test as to how well one can play is that because it is the perfect opportunity to exercise jazz language. The term ‘Jazz Language’ refers to the ability to play over common chord sequences with melodic, harmonic and rhythmic attributes that show you have studied the lineage of jazz improvisation. With a Rhythm Changes, it is possible to play almost every type of jazz language on this one form. From the chord-tone approach of the 30s swing, the chromaticism of the bebop period, the bluesy feeling from the post-bop period and the hip, angular lines of the post-coltrane/modern jazz period. We are going to listen to an example of each:

Ex. 1 – Lester Leaps In by Lester Young

Ex. 2 – Dexterity by Charlie Parker

Ex. 3 – Oleo as played by John Coltrane in the Miles 1955 Quintet

Ex. 4 – Straighten Up and Fly Right as played by Harold Mabern and Geoffrey Keezer.

So as you can here, the reason Rhythm Changes are hard is not because there’s loads of complex chords or even that it is usually played at a fast tempo rather it is because of what has gone before. It is a very tall order to master all of these different concepts of playing a rhythm changes but it is also a good way to make sure you can really do the basics before moving on to the more complex.

As you heard in the Lester Leaps In solo, Lester uses chord tones and upper extensions to improvise on, its fairly simple but very effective. This would be a good place to start.

1) Go through and make sure you can play the chord tones and upper extensions of the chords. You can’t skip over this, yes, you really must know what the 13th or #11th of G7 is or any other chord for that matter.

2) Think about how you might link the chords together horizontally. Using chromatic notes will make the transition through the chords smoother. Look for opportunities to do this. eg:

3) Make sure you know what the implications are of putting in altered dominants. Know your diminished scales for b9 and altered scales for Alt. chords.

4). Transcribe your favourite solos. I know you hear this alot but it is the only way. Learn to play the solos as close as you can to the original. Start with something that isn’t too fast. Often the reason people are scared of transcribing are the tempos and the thought that they’ll never get through it all. If you work slowly and diligently, you will. Here is an example of a Rhythm Changes solo by the great pianist Barry Harris on Charlie Parker’s Moose the Mooch. Break the solo down into ‘cells’. A cell is a small musical idea, the cell could be melodically, harmonically or rhythmically interesting. Build up a catalog of cells and then try to string them together. Once you can do this, the fun starts to happen. You’ll come up with cells that you’ve heard and cells of your own. Then you can start to work on speed and fluency.

Remember playing rubbish ideas at fast tempos is not the goal. We want to play great ideas at all tempos! Truly master each stage before moving on. Above all, listen, nobody can teach you how to swing or how to articulate better than the jazz masters themselves. Forget books, forget information-based things (such, play triplets and not dotted). You have to feel the swing in your heart and listen and copy, listen and copy.