Spike Wells Remembers…Philly Joe Jones

If I could only keep one of my Desert Island drummers (the others would have been Roy Haynes, Elvin Jones, Tony Williams, Pete La Roca, Jack Dejohnette, Tony Oxley and Bill Stewart), I’d have to choose the great Philly Joe.

And not because he’s the only drummer I’d ever had lessons with!

His playing is unmistakeable, magisterial, thrilling, hip and somehow “right”. No wonder he was Bill Evans’s favourite drummer and no wonder Miles Davis, when someone suggested he was too loud, said “I don’t care. I need his fire”.

His finest hour was obviously with the Miles Davis quintet from 1955 to 1958. But my favourite track is the simple 12-bar blues Pot Luck on the Wynton Kelly 1960 trio album Kelly at Midnight.

I make a rule of playing this to anybody who comes to me for lessons, because it not only contains the most perfectly constructed drum solo but it is also the best example I have ever heard of a totally integrated rhythm section, fusing as one man in mutual understanding and swinging like the clappers.

I first met Philly Joe when he came to live in London in 1967/8. He stayed in bassist John Hart’s flat in Hampstead and from John’s front room with a couple of chairs and practice pads (he had no kit with him and no work permit), he gave lessons to any British drummers who made the trek up Hampstead Hill. These included Alan Jackson, Bryan Spring, myself and several others.

He swore by a book called The Charles Wilcoxon All-American Drummer which contained military snare drum solos composed of rudiments, especially the paradiddles for which Philly Joe was famous. It wasn’t quite what we were expecting or possibly hoping for but he did also show me some neat little conjuring tricks with the ride cymbal beat which produced changes of tempo or time signature.

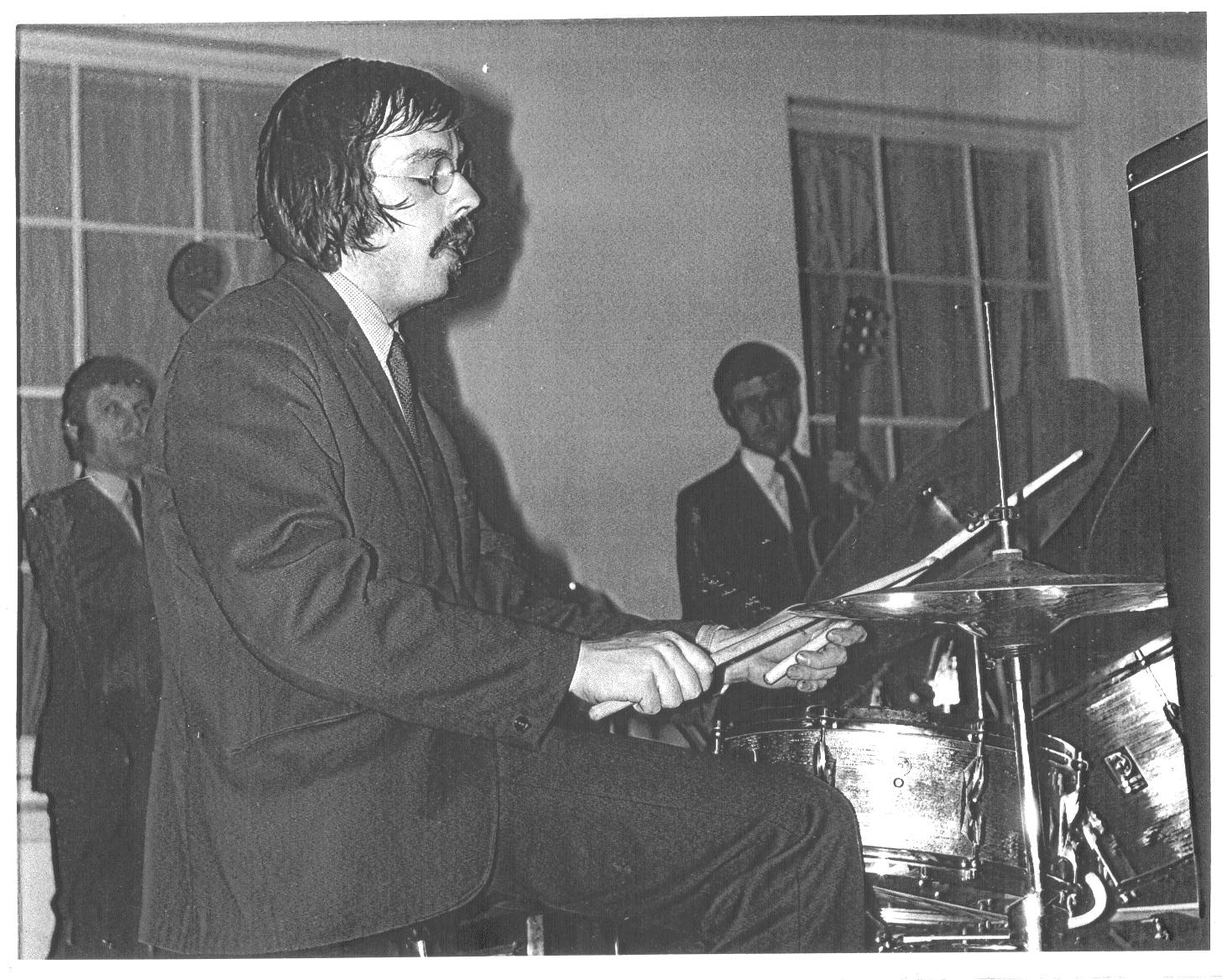

In early 1969, while Philly Joe was still in town, Premier Percussion promoted a concert tour of the country, featuring the Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland big band, the Roland Kirk quartet and the Philly Joe Jones trio. Kirk needed a rhythm section and Ronnie Scott’s club recommended Mike Pyne, Ron Matthewson and myself who were working together with Tubby Hayes at the time.

So I found myself in the awesome company of two of the greatest American drummers in history plus the superb British big band drummer Kenny Clare. It was wonderful to hear Philly Joe every night (yes! he finally had a kit to play – Premier insisted we all play their own brand which was fine) and Kenny Clarke was also very friendly and encouraging, jotting down figures and suggestions for me on scraps of paper.

We all travelled in one band bus, on which life was pretty surreal. Kenny Clarke sat right up front, smoking all sorts in his venerable pipe; Philly Joe was zonked out in the back; Johnny Griffin paced up and down the aisle jiving with everybody, Roland was making weird noises with some of his “toy” instruments. My seat was next to Ellington bassist Jimmy Woode who was delightful company.

When we made a small-hours stop for a fry-up at the old Blue Boar service station at Watford Gap, Philly Joe arrived at the till with his blanket over his head, gave a Red Indian salute and greeted the long-suffering check-out girl with “HOW!” The world-weary response was “Yer what, luv?”.

I last met Philly Joe at a jazz festival in Norway in 1976 (where I was working with John Taylor). My first sight of him was at the luggage carousel in the airport. He stood regally waiting for his cymbals, overcoat casually draped across his shoulders and smoking a king-size cigarette. He was appearing with Sonny Stitt who had not at that period permanently dried out and was truculently drunk on stage the night of their first set.

The next day, I was talking to Philly Joe when we saw Sonny approaching. “Here we go” he said in a conspiratorial whisper, “just wait – ’I’m sorry, baby. I won’t do it again tonight’ ”.

And moments later: “Stitt my man, how you feelin’?”

“Aw, I’m so sorry, baby. I won’t do it again tonight.”

Spike Wells